This is a term I was reminded about when having a tutorial with Dan. It took me back to an earlier module (https://garyphilodesign.co.uk/week-6/) where I learnt about noticing the ignored and the term “derive”, created by the situationists.

The situationists’ wanted to highlight the way in which everyday life is controlled through the geographical environment and not through individual desires and behaviours.

Gary Philo

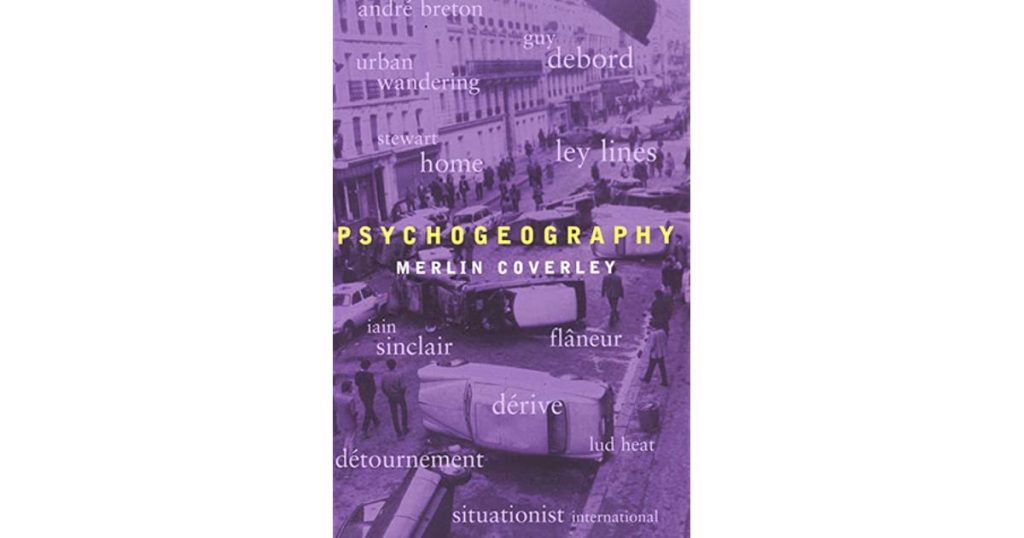

Psychogeography – Merlin Coverley

This led me to research the subject further to understand how psychogeography had developed since the 1950s. I came across this book:

Coverley explains how psychogeography is a “term that has become strangely familiar – strange because, despite the frequency of its usage, no one seems quite able to pin down exactly what it means or where it comes from.” and how it is “constantly being reshaped by its practitioners.”

He, of course, also notes the impact Guy Debord and the situationists influence on the subject and reiterates their own definition of the term:

The study of the specific effects of the geographic environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviours of individuals.

Guy Debord, ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography”

With that in mind, in its simplest terms, Psychogeography is where psychology and geography meet and how one affects the other. The term has been used by many researchers, authors and explorers since the 1950s and they have reappropriated that word, playing with its meaning to establish new ways in which we engage and interact with our environment. And you know what? That’s OK. Even Debord described the word as having a “pleasing vagueness”.

A key characteristic of psychogeography is that of walking or wandering. Most psychogeographers are concerned with walking in urban environments – mainly cities – and this is because it is there where walking is the main, and quickest, mode of transport.

I think it is this “street-level gaze” which increases this directional and emotional subversion. How often have you seen a commuter with their nose stuck in a book or their phone, briefly looking up to acknowledge they are on the right track before returning to their own, controllable environment?

I would, therefore, argue that places, where pedestrianism is an active choice, mean people ‘look up’ more. They are more affected by the environment and are more intrinsically part of the world around them.

Coverley continues to describe psychogeography as having a “history of ironic humour.” – Sounds right up my street! I suppose if you don’t notice the ignored the world around you can seem quite banal and by highlighting the unusual and ‘unseen’ in a humourous way, you create a sense of interest that “reveals the true nature that lies beneath the flux of every day.”

With a variety of psychogeologists providing slightly different viewpoints and approaches to the phenomenon, Coverley looks at some of the most influential characters and how they differ.

JG Ballard, who “was an English novelist, short story writer, satirist, and essayist”, and Coverley says that his work, “clearly demonstrate(s) that it is the novelist rather than the theoretician who is best able to capture the relationship between the urban environment and human behaviour.” Although Ballard shares similar thoughts to the Situationists – in that they both believe in the “banalisation of everyday life” or “loss of emotional sensitivity” – however, Ballard seeks to challenge this idea or ‘boring’ by focussing on the extremes in behaviour that can result from people trying to feel again.

Peter Akroyd developed a notion of ‘chronological resonance’ which is the idea that space is somewhat governed by history. Although in his own words, “The nature of time is mysterious…..Sometimes it moves steadily forward, before springing or leaping out. Sometimes it slows down and, on occasions, it drifts and begins to stop altogether.” (Peter Akroyd, London: The Biography, p661)

Stewart Home, a key figure in the London Psycogeographical Association, has carved out a reputation for highlighting “violent, sexually graphic theoretically alert accounts of London lowlife.” He is also known as a “wind-up merchant” and uses a knowledge of psychogeographic history and a unique, almost confrontational approach, creates an interesting style which warrants further exploration. Anyone whose work gets described as, “extremely, entertaining bollocks” (NME, Confusion incorporated, rear cover), must be researched further!

Will Self

Synopsis:

Provocateurs Will Self and Ralph Steadman join forces in this post-millennial meditation on the vexed relationship between psyche and place in a globalised world, bringing together for the first time the very best of their “Psychogeography” columns for the “Independent”.

Whilst this book provides an interesting read and shows the detail and wit which can be implemented in the escapades of psychogeography, I don’t feel it furthers my research. Nevertheless, I did read and enjoy the book and I hope that some of the vernacular and style influence my essay and final project.

Leave a Reply